ECG Case 126

A 43-year-old male is brought in by ambulance after being found unconscious following a suspected overdose. With paramedics he is GCS 3. HR 70, BP 109/65, RR 10, SpO2 100 on 15L O2.

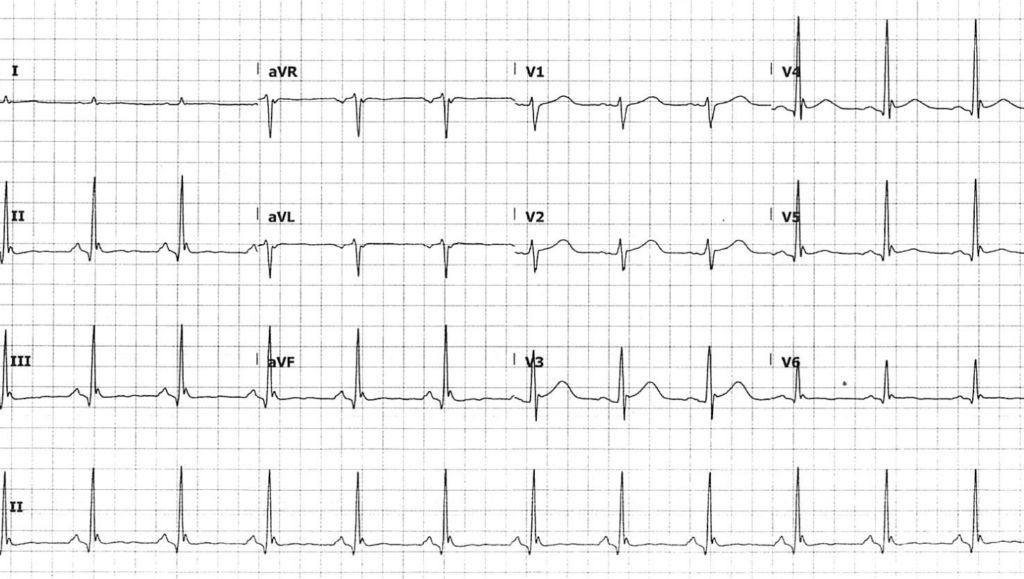

An ECG is taken on arrival to the resuscitation bay:

Describe and interpret this ECG

ECG ANSWER and INTERPRETATION

This ECG demonstrates many of the classical features of hypothermia:

- Prominent J waves (Osborn waves) seen best as a positive deflection in V4 and V5, and a negative deflection in aVR

- QT prolongation, with an absolute QT interval of ~520ms

- T wave flattening in lateral precordial and inferior leads

This patient had a core temperature of 28°C (82.4°F)!

Whilst initial rewarming therapy is commenced, a venous blood gas is taken:

What is your interpretation of the VBG?

Reveal answer

- There is a concurrent profound respiratory acidosis and high anion gap* metabolic acidosis

- In acute respiratory acidosis, we expect a rise in HCO3 concentration of 1mmol/L for every 10mmHg rise in pCO2 above baseline 40mmHg

- Expected HCO3 value here in a sole acute respiratory acidosis would be 33 mmol/L. A value of 25 suggests a concurrent primary metabolic acidosis, likely secondary to hypoperfusion and lactaemia in the context of hypothermia

*Anion gap= Na – (Cl + HCO3). Normal range 4-12 mmol/L.

Note that acidaemia and hypercapnoea will appear exaggerated in a warmed blood gas from a hypothermic patient:

- Higher gas solubility at lower temperatures leads to lower effective partial pressures of CO2 and O2

- Warming a sample to 37°C releases more gas, and partial pressures will appear higher than those actually present in the patient’s blood in vivo

- Corrected values here are a pH of 7.045 and a pCO2 of 110mmHg

Read further on interpretation of arterial blood gas results in hypothermia.

PROGRESS

With clinical and radiographic evidence of aspiration, and severe type 2 respiratory failure, this patient was intubated for airway protection and ventilation purposes. Active external and internal warming was commenced along with fluid resuscitation and a 10% IV dextrose infusion.

He was successfully rewarmed to 33°C without initial complication, with resolving acidaemia. Approximately three hours into his stay he became acutely hypotensive with a MAP of 40mmHg.

A bedside echo was performed:

What is your interpretation?

Reveal answer

- Apical four chamber view

- Image quality is suboptimal, angling posteriorly through the coronary sinus and apex, which can lead to underestimation of ventricular size and overestimation of function

- There is moderate LV systolic dysfunction. Chamber size was measured normal

- TAPSE was measured at 0.8cm, indicating at least moderate RV systolic dysfunction

- A trace (physiological) pericardial effusion is seen at the apex

PLAX and PSAX view were difficult to obtain due to ventilation and inadequate to comment on function.

OUTCOME

MAP responded well to a combination of noradrenaline (improves vasodilation, weak inotropy) and adrenaline (for additional inotropy). Bedside echo 24 hours post admission revealed similiar findings of moderate biventricular systolic impairment despite this therapy. A formal echo on day 2 of admission demonstrated complete resolution of these abnormalities.

This transient global hypokinesis was thought to be due to myocardial stunning, as part of a post-cardiac arrest syndrome.

CLINICAL PEARLS

Post-cardiac arrest syndrome

Post-cardiac arrest syndrome, also known as post-resuscitation syndrome, reflects a state of whole body ischaemia and subsequent reperfusion injury. Components include neurological dysfunction, transient myocardial dysfunction (myocardial stunning), and a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).

In early reperfusion following cardiac arrest or severe hypoperfusion, the heart is initially hyperkinetic due to circulating catecholamines, with ensuing global hypokinesis. This transient myocardial dysfunction is responsive to inotropic drugs and usually resolves within 24-72 hours. Coronary blood flow is not reduced, indicating a true stunning phenomenon rather than permanent injury or infarction.

Note that this is a diagnosis of exclusion, and we must rule out other conditions including acute coronary syndrome prior to attributing cardiac dysfunction to post-cardiac arrest syndrome.

Hypothermia and repolarisation abnormalities

ECG changes in hypothermia relate to slowed potassium efflux in phase 1 and 2 of the cardiac action potential, correlating with early membrane repolarisation. This results in predominantly ventricular repolarisation abnormalities, manifesting on the ECG as prominent J waves, QT prolongation, and loss of normal T wave morphology. Bradycardia is common and may be the only initial feature.

Complications of rewarming

Disproportionate hypotension often occurs during rewarming, due to a combination of severe dehydration, fluids shifts, and peripheral vasodilation as a result of active external rewarming. An after drop in temperature is common and was seen in this patient — when the extremities are rewarmed, cold, acidaemic blood that has pooled in vasoconstricted extremities of the hypothermic patient returns to core circulation, causing a drop in temperature and pH. This can theoretically predispose to arrhythmias but usually is clinically insignificant. Focussing active external rewarming on the trunk can reduce these complications.

Failure to rewarm should raise suspicion for other contributing causes of hypothermia, including sepsis (especially in the elderly patient), adrenal insufficiency, and hypothermia.

Electrolyte concentrations can be unpredictable during rewarming and should be closely monitored. Severe hypothermia (< 30°C) is associated with insulin resistance, and these patients are predisposed to hypoglycaemia on rewarming as insulin sensitivity normalises. It would be prudent to give a glucose infusion (100ml/hour of 10% dextrose) until core temperature is above 34°C.

Cardiac function in hypothermia

There are sparse human studies on the effects of hypothermia on myocardial contractility. Limited studies in patients undergoing cardiothoracic surgery suggest there is little change in left ventricular contractility with cooling to 32-34°C, but beyond this point both contractility and heart rate fall leading to substantial reductions in cardiac output. Due to slowed metabolism and peripheral vasoconstriction, lower cardiac output is required to maintain vital organ perfusion in hypothermic patients.

Further reading

Related topics

- ECG changes in hypothermia

- Osborn Wave (J Wave)

- Nickson C. Arterial Blood Gas in Hypothermia. LITFL

- Nickson C. Hypothermia: Overview and Management. LITFL

- Fennessy G. Post-cardiac Arrest Syndrome. LITFL

Expert review

- Smith SW. Massive Osborn Waves of Severe Hypothermia. Dr Smith’s ECG Blog. 2015 January

References

- Haase et al. Variability in Glycemic Control with Temperature Transitions during Therapeutic Hypothermia. Crit Care Res Pract. 2017;2017:4831480

- Filseth et al. Post-hypothermic cardiac left ventricular systolic dysfunction after rewarming in an intact pig model. Crit Care 14, R211 (2010)

- Lewis et al. The effects of hypothermia on human left ventricular contractile function during cardiac surgery. 2002 Feb. JACC. 39(1):102-8

TOP 150 ECG Series

MBBS (UWA) CCPU (RCE, Biliary, DVT, E-FAST, AAA) Adult/Paediatric Emergency Medicine Advanced Trainee in Melbourne, Australia. Special interests in diagnostic and procedural ultrasound, medical education, and ECG interpretation. Editor-in-chief of the LITFL ECG Library. Twitter: @rob_buttner

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at the Alfred ICU in Melbourne. He is also a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University. He is a co-founder of the Australia and New Zealand Clinician Educator Network (ANZCEN) and is the Lead for the ANZCEN Clinician Educator Incubator programme. He is on the Board of Directors for the Intensive Care Foundation and is a First Part Examiner for the College of Intensive Care Medicine. He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives.

After finishing his medical degree at the University of Auckland, he continued post-graduate training in New Zealand as well as Australia’s Northern Territory, Perth and Melbourne. He has completed fellowship training in both intensive care medicine and emergency medicine, as well as post-graduate training in biochemistry, clinical toxicology, clinical epidemiology, and health professional education.

He is actively involved in in using translational simulation to improve patient care and the design of processes and systems at Alfred Health. He coordinates the Alfred ICU’s education and simulation programmes and runs the unit’s education website, INTENSIVE. He created the ‘Critically Ill Airway’ course and teaches on numerous courses around the world. He is one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) and is co-creator of litfl.com, the RAGE podcast, the Resuscitology course, and the SMACC conference.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Twitter, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC