The grandest spaces in the whole of the mighty Victoria and Albert Museum are the Cast Courts, built high enough to hold a full-scale replica of Trajan’s Column in Rome, which is colossal even in two pieces. No less imposing are the London museum’s 19th-century copies of Michelangelo’s David, not to mention its duplicates of Viking carvings and even the entire front of a Spanish cathedral. All these casts, which were recently cleaned, are a curious spectacle. Why did the Victorians create such a comprehensive “virtual art” collection? To make a clever point about a copy being just as good as the real thing – or simply to bring great work to the people?

But there’s one exhibit here that brings the world of the fake, and all the questions the subject provokes, up to date: an eerily precise 3D print of a nude statue of Pauline Bonaparte, sister of French military leader Napoleon, by the neo-classical artist Canova. This lovely replica is the work of British-born, Madrid-based artist and tech pioneer Adam Lowe. By placing it here, the V&A is recognising that Lowe is reinventing the much misunderstood practice of copying. Indeed, Lowe takes the fine art remake to such heights of accuracy, sensitivity and detail that even experts are fooled. Far from being derided as cynical forgeries, though, his copies are hailed by this and other museums as opening up new ways of understanding and enjoying masterpieces.

Lowe’s latest project, which will be unveiled after this second lockdown, sits at the other end of the V&A, past Buddhist sculptures and the busy shop – in the gallery that houses its most precious treasures, the Raphael Cartoons, which have been on loan from the Royal Collection since 1865. These huge, full-size designs for tapestries in the Sistine Chapel depict scenes from the lives of Saint Peter the Apostle and Saint Paul. In one beautifully detailed work, The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, Christ is telling Peter to cast his nets into the water, whereupon he and his fishermen make a mighty catch.

Lowe calls these works “the greatest Renaissance paintings outside Italy”. In which case, you might expect them to be more popular. Displayed in low light and lost in the vast Raphael Court, these rich creations go largely unnoticed. During a Day of the Dead event I attended, crowds were making masks and watching performances without even a glance at the Raphaels soaring up the walls around us. Something needed to be done – especially as 2020 is the 500th anniversary of Raphael’s death, reputedly from sexual exhaustion, at the age of 37.

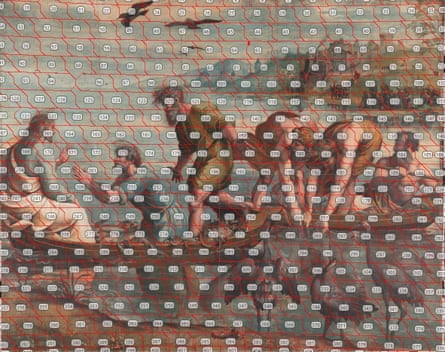

So a virtual version of the cartoons has been created by Lowe and his Madrid workshop Factum Foundation, to bring Raphael’s subtle detailing much closer and make his genius shine out again. There in the Raphael Court, visitors will be able to compare the actual cartoons with hypnotically exact closeups by exploring Lowe’s digital scan on monitors. His creations will also go online so that, should the museum close again, you can still get intimate with Raphael at home. There will hopefully never be any need to go further, but the cartoons could be recreated physically from this digital record.

Brought to Britain by Charles I in the early 17th century, the cartoons survived the civil war that cost the monarch his head. They also survived fire-prone and damp royal palaces and, since coming to the V&A, two world wars. But in these feverish times, the digital recording of art feels all the more urgent as we glimpse how quickly things fall apart, how swiftly it can become impossible to experience art in the here and now.

“Since Covid started,” says Lowe, “we’ve been busier than ever.” As Italy descended into crisis earlier this year, a Raphael anniversary exhibition opened in Rome for which Lowe created an eye-fooling, full-scale replica of the artist’s elaborate marble tomb. By the early summer, he was roaring out of lockdown to make copies of early paintings by Velázquez for a new museum at the great Spanish painter’s Seville birthplace.

The way he talks about Velázquez’s An Old Woman Cooking Eggs – which his team have scanned in the Scottish National Gallery to remake back in Madrid, where the painter died – reveals what makes him so unusual. He’s a true art lover. Velázquez was just 17 when he painted this but, enthuses Lowe, he is the equal of Caravaggio when it comes to hypnotic realism. “I love the garlics and the red onions,” says Lowe, who insists he is not trying to replace the original but reveal it. “We’re not trying to forge An Old Woman Cooking Eggs. What we are doing is a celebration of understanding: to see it afresh.”

There are other people producing “perfect” digital images and 3D printed replicas. What makes Lowe different is that he’s also an artist, and his use of machines is always tempered by the human touch. He’s a trained painter who had his own career in art before founding his company Factum Arte, one of the leading “fabricators” of contemporary art, mixing digital magic and manual craft to realise the ideas of Marina Abramović, Grayson Perry, Anish Kapoor and others. When he makes tapestries for Perry, he does not just draw on his time spent micro-photographing Raphael’s great tapestry designs, he also brings his own artistic intuition.

One of Lowe’s most delicate jobs was to make a new version of Caravaggio’s Nativity. Stolen by the mafia in 1969 and probably lost for ever despite sporadic bursts of hope, this great painting left a blank space in the Oratory of Saint Lawrence, Palermo. When Factum was commissioned to fill that hole, the team had to enhance and restore a 1960s photograph, combining it with the results of closeup scans of surviving works by Caravaggio. Then a printed copy was retouched by brush, Lowe himself stepping up for this task. The result is not a fake, nor a full substitute, but something that has given Palermo a piece of its heart back.

Lowe happily acknowledges “the obsessive nature” of his projects. His passion struck me the first time I met him, in front of The Last Supper in Milan, where he was working with film-maker Peter Greenaway on an art event about Leonardo da Vinci’s eerie, eroded mural. Lowe created a huge facsimile of its surface, which is actually just a massive field of fragmented paint flecks. Like our obsession with this ghost of a painting, the experience was slightly surreal. What struck me most was his huge enthusiasm, his sense that he’s giving the world something new.

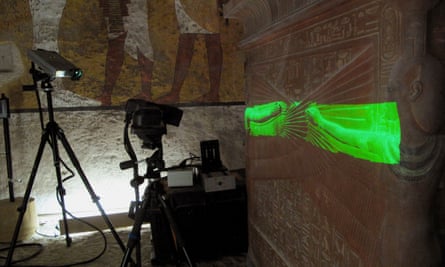

While Lowe sometimes seems to do his work just for fun, there is also a social and cultural benefit. From their scans of Tutankhamun’s tomb, his team produced a replica that you can now visit in the Valley of the Kings without damaging the original. Another project involves scanning the Tomb of Seti I, one of the best decorated tombs in the valley, but now almost always closed to the public due to damage. Lowe is proud that the team working on it are entirely Egyptian. “They are all from the West Bank in Luxor,” he says. “We’re helping local people to preserve their own heritage.”

This echoes one of his proudest achievements: recreating a precious rock art site in the Amazon after it was mysteriously vandalised. The painted cave of Kamukawaka is the Bible of the Wauja people, not just art but their story of who they are. His team worked closely with them to remake it, resulting in a lifelike resin copy of part of the actual cave with its lost inscriptions reborn.

To see one of these micro-precise replicas of an entire cultural site, or a sizeable piece of it, can be mind-blowing. And sometimes galleries get more than they bargained for. When the National Gallery in London commissioned Lowe to reproduce a curved painted niche from a church in Rome, the results included a 3D plug socket that some fool had put in the middle of the original fresco. But perhaps the most radical achievement of Factum, and one that’s acutely welcome in our new world of lockdown, is the way its creations can dissolve museum walls and reconnect their treasures not just with new audiences but with the raw, real world they came from. Lowe is certainly no fan of the way great art gets isolated and fetishised.

“All those people taking selfies in front of the Mona Lisa,” he says, with a shake of his head. Lowe’s bothered by the fact that visitors to the Louvre in Paris will queue for hours to see arguably the world’s most famous painting in its glass tank – and not even notice a comparably beautiful, and much bigger, Renaissance painting nearby: Paolo Veronese’s wall-filling epic canvas The Wedding Feast at Cana, showing Christ turning water into wine. It hangs in the same gallery yet it is lost, despite its size, in the clamour to see Leonardo’s work.

“What the hell would Veronese think if he wandered into that room?” says Lowe. He’d be perplexed, because museums didn’t exist in his day. He painted The Wedding Feast at Cana for a particular place: the monks’ refectory of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice. If only we could see it there. Well, we can – for Lowe has created a facsimile to hang in the place where Veronese’s original would have been.

“Think how many masterpieces are smashed up,” says Lowe. Quite – the National Gallery is full of panels wrenched from churches where they once loomed in flickering candlelight, being prayed to and wondered at. They then become “art” in a clean sensible setting, amid white walls and carefully calibrated lighting. The possibilities revealed by Lowe and Factum are endless: while a museum preserves the fragile original, a perfect replica can show what it looked like in its original setting. This puts flesh on the past, lets us experience art as part of life. Great statues, frescoes and even entire chapels can be recreated anywhere, plug sockets and all.

When I ask Lowe what he loves about Raphael, he mentions the Stufetta del Cardinal Bibbiena, a luxury bathroom the artist created in the Vatican complete with pagan erotic frescoes. This decadent hideaway is in the Pope’s chambers, not on view to the public. Perhaps the V&A should commission Lowe to replicate it: I can’t think of a better way to bring art alive than letting us all use Raphael’s loo. Lowe laughs and nods. “While Leonardo was inventing war machines,” he says, “Raphael was inventing the flush toilet.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion