OKLAHOMA CITY — There is a war raging across the United States on the role of religion in public life, and Ryan Walters is at the center of it.

As Oklahoma’s elected official in charge of public education, the conservative Republican and outspoken Christian has been at the forefront of encouraging closer entanglement between government and religion when it comes to one of the most contentious places of all: public schools.

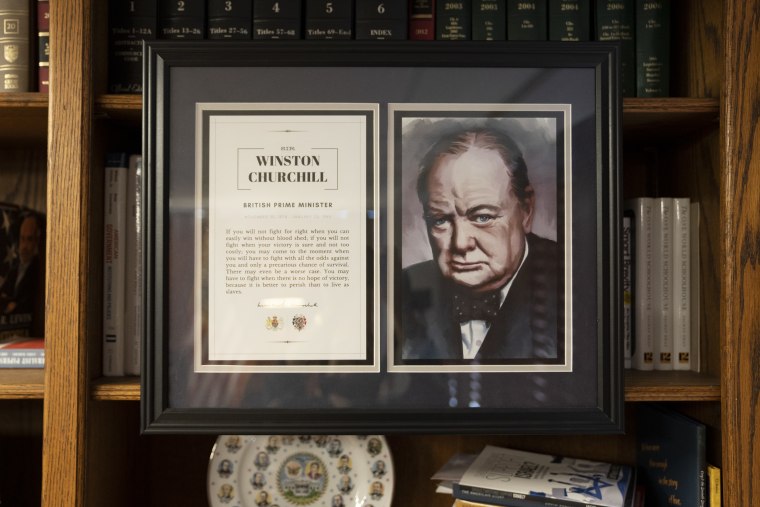

“What I’m trying to make sure is our kids understand American history,” Walters said in an interview in his office in Oklahoma City, which is decorated with images of one of his heroes, Winston Churchill.

“I do want them to understand American greatness. I want them to understand American exceptionalism. I want them to have the freedom to express their religious beliefs in schools,” he added. “I believe that’s very important. I believe that’s been absolutely gutted from our school system.”

Under Walters’ watch, the state approved the first ever religious virtual public charter school, a provocative move that is now before the Supreme Court, which will hear oral arguments on the constitutionality of the move next month. He has also proposed placing Bibles in schools, a move that was recently blocked by the state Supreme Court, and is seeking to add more Christian-related themes to the curriculum, including information about the Ten Commandments.

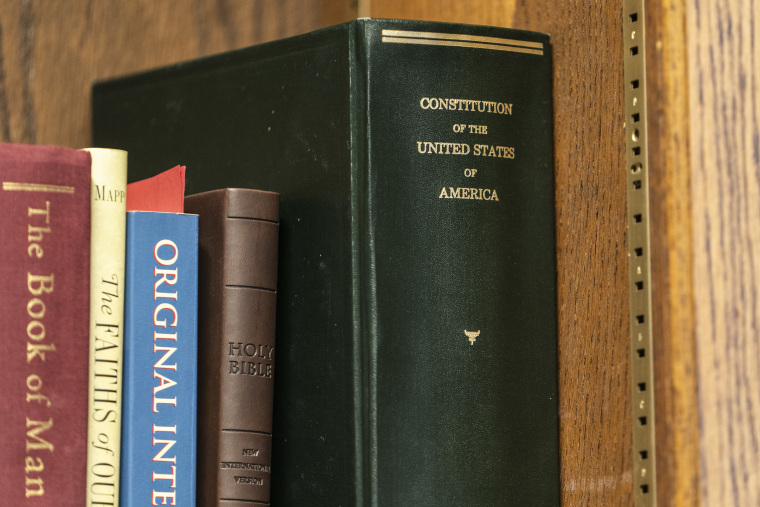

At the heart of the religious school case and others like it is the Constitution’s First Amendment — and two provisions about freedom of religion that are in tension with each other. They are the establishment clause, which forbids the government from endorsing one religion over another or setting up its own church, and the free exercise clause, which says everyone has a right to express their own religious beliefs.

Generations of children were taught in school about how Thomas Jefferson said in an 1802 letter that there is “a wall of separation between church and state.” In the past, the Supreme Court interpreted that sentiment broadly, and government officials, including those running public schools, followed suit. Any actions that could potentially be interpreted as a sign that the government endorsed religion were largely off-limits.

Now, the religious school case from Oklahoma could change the longtime understanding of the First Amendment throughout the U.S.

Walters and others like him believe that the Supreme Court got it wrong in the past. They point out that the First Amendment itself says nothing about a “wall of separation” and focus more on their rights under the free exercise clause.

As for the Supreme Court, it now has a 6-3 conservative majority that strongly favors religious rights and in a series of recent decisions has strengthened the free exercise clause, sometimes at the expense of the establishment clause.

But even in deep-red Oklahoma, where President Donald Trump won every county in last year’s election, not everyone is on board with Walters’ hope to water down the establishment clause.

Notably, state Attorney General Gentner Drummond, a fellow Republican, vigorously opposes the religious schools plan, to the extent that he filed his own legal challenge against it, which is what led to the Supreme Court’s involvement.

“We deserve intellectual honesty on this issue. It’s about religious indoctrination,” he said in an interview.

Drummond agreed that attempts to allow prayers in schools could be next on the agenda if the Supreme Court endorses the school proposal.

“The Supreme Court can decide how far it wants to go,” Drummond said.

Walters, a former high school teacher, strongly supports the charter school plan, which would funnel taxpayer dollars directly to an entity controlled by the Catholic Church.

But, as his Bible distribution plan shows, he doesn’t want to stop there.

He told NBC News he also believes the Supreme Court’s landmark 1962 Engel v. Vitale ruling that outlawed prayers in public schools should be overturned. The court held in a case arising from New York that the reading of a nondenominational prayer in class, in which students were not required to participate, violated the establishment clause.

The ruling is considered to be such a milestone that it features in high school Advanced Placement government classes, which Walters himself taught, and in the federal judiciary’s own educational materials.

“I think they were dead wrong on that. Individuals have the right to express their religious beliefs. That does not stop in a school building,” Walters said of the decision.

‘Aha moment’

The Covid-19 pandemic, which forced schools across the nation to quickly move operations online, was the genesis of the plan to start a Catholic virtual charter school, according to Michael Scaperlanda, a former law professor who is now chancellor of the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City.

There are already brick-and-mortar Catholic schools in Oklahoma, but they are in urban areas in what is a largely rural state.

But the ease with which schools were able to pivot to online education was an “aha moment” for church officials, Scaperlanda said in an interview at the grand, recently constructed shrine in Oklahoma City that honors Stanley Rother, an Oklahoma-born Catholic priest who was killed in Guatemala.

At that point, Oklahoma’s Statewide Charter School Board was already established and had approved both in-person and virtual nonreligious schools. The church saw an opportunity both to set up a virtual school and find a way to fund it.

It was obvious it would spark a legal challenge, but in consultation with Nicole Garnett, a professor at Notre Dame Law School who along with other conservatives has long argued in favor of religious charter schools, the archdiocese thought it was worth a shot.

One consideration was the Supreme Court’s full-throated support of religious rights.

“Given the fact that we had this virtual charter opportunity in Oklahoma coupled with the way the court was looking at religious liberty, it looked like an opportune time to apply,” Scaperlanda said.

“We weren’t looking for the fight, but we were prepared for it if it came,” he added.

At the time, the plan for what was named St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School had the backing of Oklahoma’s then attorney general, John O’Connor. At the request of the charter school board, he submitted a legal opinion in December 2022 saying that in his view a religious charter school would be lawful.

An application jointly proposed by the Oklahoma City and Tulsa archdioceses was officially submitted in early 2023, and the school was approved that summer. As a result of the litigation, it has yet to open its virtual doors.

The school’s lawyers argue that under the free exercise clause, the state cannot block the proposal, while opponents say that the establishment clause forbids Oklahoma from funding the new school.

Drummond, who took office in January 2023, filed his lawsuit in the fall of 2023. He won before the Oklahoma Supreme Court, which said the proposal was barred under both the Oklahoma and U.S. constitutions. That prompted the charter school board and the school to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The opposition is not limited to Drummond. Another lawsuit came via several individual plaintiffs who oppose state-funded religious schools. They are represented by Americans United for Separation of Church and State, a legal group that advocates for keeping religion out of government.

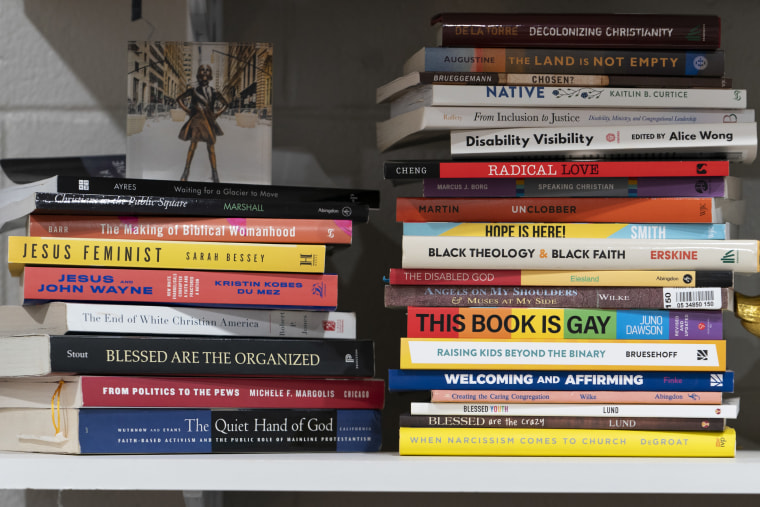

Lori Walke, a minister at Mayflower Congregational United Church of Christ in Oklahoma City, is one of those plaintiffs. The congregation leans left, with a sign featuring the LGBTQ pride flag hanging on the entrance lobby wall.

“Here in Oklahoma, we seem to be the training ground for Christian nationalism,” Walke said in an interview in her cozy office a few steps from the church’s simple, white-painted sanctuary. A sign saying “nobody’s free until everybody’s free” hung behind her desk.

“Christian nationalism” is a loose term some have applied to conservative Christians who want to open up government spaces to religious, and specifically Christian, speech and symbolism. Critics like Walke say the aim of Christian nationalists is to impose their religious views on others.

“When I heard that this religious institution was insisting that it be given taxpayer dollars to indoctrinate and coerce and discriminate, my first response was that people of faith had to rise up and be the bulwark that defends our families and our public schools,” Walke said.

Another plaintiff, Erika Wright, sees the fight as being primarily about protecting rural schools in the state. She lives in the town of Noble, about an hour south of Oklahoma City, and currently has two kids in public school.

Speaking in her spacious house outside of town, an antique hunting rifle hanging over the mantelpiece, she explained how she heard about the Catholic school idea early on through her work with the Oklahoma Rural Schools Coalition, a public education advocacy group.

The most worrying thing for her about approving religious public charter schools is “the door that this opens to really depleting and diverting crucial resources from our public schools,” she said.

Wright, who is a Republican, said there are more than a dozen churches in her area that already do a good job of providing religious instruction to young people.

“We have enough Sunday schools around here,” she said.

Constitutional tension

The Oklahoma case will go before a Supreme Court that has in recent years rolled back strict, longtime boundaries on government involvement with religious entities.

As a result, the court has been inundated with cases brought by religious groups seeking to dismantle, brick by brick, the “wall” that Jefferson described.

Nowhere is that more apparent than education, where advocates for school choice — who want education funds to follow their children into private, often religious schools — are eager to remove legal obstacles.

In doing so, the court has rejected arguments made by government entities that the establishment clause requires them to stay out of religion altogether.

“The goal is that religion should be left to the private choices of individuals,” said Luke Goodrich, a lawyer at religious rights group Becket. The government “controls so many levers of power” that it is easy for its actions to infringe upon religious liberty, he added.

The current Supreme Court views the establishment clause through a historical lens dating back to the founding, Goodrich said. Then, it had a limited and defined meaning that was aimed at preventing government control over churches and religious exercise and nothing more, he added.

That interpretation is fiercely contested.

“It’s a lie about American history,” Rachel Laser, president of Americans United, said in an interview.

“We are witnessing what it looks like for the establishment clause to be weakened. The sad thing about that is that the establishment clause and free exercise clause work together in healthy tension to protect religious freedom for all,” she added.

The Supreme Court’s conservative majority has been receptive to the arguments made by the likes of Becket and Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF), a conservative Christian group that represents the Oklahoma charter school board in the upcoming case.

In one series of three related cases, the court — with liberal justices often opposed — opened the door to taxpayer money flowing to religious entities, including schools, in certain circumstances. These cases are repeatedly cited by the lawyers defending the Oklahoma school proposal.

The court first ruled in 2017 on a 7-2 vote that a church in Missouri could not be denied access to a state program that helps nonprofit groups fund playground improvements. That was followed by a 5-4 ruling in 2020, citing the earlier decision, that endorsed a Montana program allowing tax credits to be used to help children attend religious schools. Two years later, the court ruled 6-3 that Maine could not exclude religious schools from a tuition assistance program for people living in rural areas that have few educational options.

Marci Hamilton, a professor who studies religion at the University of Pennsylvania, said these rulings were the result of a concerted effort by conservative lawyers and law professors to reinterpret the religion clauses of the First Amendment to focus on the notion that barring religious entities from government programs is a form of discrimination in itself.

“This has been the intent from the beginning, and the idea is that from there on out, any barriers to funding from the government to religion were unfair because they were supposedly discriminatory,” Hamilton said.

The legal arguments arose from legal scholarship, with Stanford Law School professor and former federal judge Michael McConnell being one key figure.

In other cases, the court, with liberal justices often signing on, has also signaled that government officials have sometimes gone too far in seeking to avoid the appearance of endorsing religion under the establishment clause.

Recent rulings included one in 2019 on a 7-2 vote that endorsed a cross-shaped war memorial in Maryland. In a 2022 case, the court ruled 6-3 in favor of a public high school football coach who was suspended for leading Christian prayers with players on the field after games, with the court’s three liberals dissenting. The same year, the court faulted the city of Boston for barring a Christian group from flying a flag at city hall under a program open to groups of all types across the city. The vote was 9-0.

The football coach case was notable because the court disavowed a 1971 precedent that set a test for determining whether government actions violated the establishment clause. Instead, the court embraced a more permissive approach based on whether the challenged conduct is based on historical practices and traditions.

One wrinkle in the Oklahoma case is that Justice Amy Coney Barrett, part of the conservative majority, is not participating. She did not explain why, but it may be because of her ties with Notre Dame Law School, where she was a law professor for many years. She is friends with Garnett, and Notre Dame’s religious liberty clinic is representing the school.

If the court were to split 4-4, the Oklahoma Supreme Court ruling that went against the school would remain in place.

Whatever happens in the Oklahoma case, more religious rights cases touching upon the establishment clause are on the horizon. Litigation is already underway over a law in Louisiana that would require public schools to display the Ten Commandments. A federal judge blocked the measure.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court will be hearing arguments on April 22 in another case touching upon religion and schools, when it hears a claim brought by parents of elementary school students in Maryland who objected on religious grounds to books available in classrooms that included information about LGBTQ issues.

The justices have also taken up a case, which is being argued on Monday, about whether the religious rights of a Catholic Church-affiliated charitable organization were violated when the state of Wisconsin required it to pay into the state’s unemployment tax system.

What remains unknown is how far the Supreme Court is willing to go in expanding individual religious liberties under the free exercise clause at the expense of the establishment clause.

Individual conservative politicians like Walters and groups like ADF are willing to push as far as they can.

“There is no such thing as a wall,” said John Bursch, one of ADF’s lawyers, referring to Jefferson’s phrasing from his 1802 letter. “My personal hope is that the Supreme Court will recognize there’s no wall there.”

But Bursch said ADF would be “leery of compelled student prayer,” for example. The establishment clause, he added, “does good and important work.”

Notre Dame’s Garnett said a lot of disputes that arise reflect “an outdated understanding of the establishment clause” that the Supreme Court has left behind.

But old habits die hard.

“The wall image, which is not in the Constitution, has powerful cultural resonance even though it wasn’t the right image,” she added.

Americans United’s Laser views the conservative reappraisal of the establishment clause as nothing less than a threat to democracy because it would grant “special power and privilege for a select few.”

In the education context specifically, she sees a clear connection between the school choice movement that has long sought to send taxpayer funds to private schools and the push for greater religious involvement in the public sphere.

“Christian nationalists are clear they want to replace public education with religious education because it indoctrinates a new generation of Americans in their faith and their lie that America was supposed to be a Christian nation,” she added.

An uncertain road ahead

The differing interpretations of what the establishment clause should mean are on stark display in Oklahoma.

Walke, whose church embraces social justice causes, finds no common ground between her idea of Christianity and what conservative like Walters espouse, saying that Christian nationalism “is an ideology that insists on a particular kind of Christianity being practiced, and not simply practiced in the home, but also expressed as a form of government.”

In his office in the modernist-style state education building a few miles across town, Walters sidestepped a question over whether he considers himself a Christian nationalist, saying it means different things to different people.

“What I believe is that the Founders believed it was essential for the future of this country that we protect religious liberty,” he said. “And I was elected to help protect that religious liberty that’s come under attack in our school system.”

Returning to the issue of prayer in schools, Walters said he saw the long-standing prohibition as part of a “war against Christianity” that has prevented people from expressing their religious views.

“We have to make sure that no one in a public school system ever sees another individual pray,” he added. “I think that’s an absurd position that is not in line with the Constitution.”